2013 City Heat Map: Property value assessment per acre

Tompkins County has a lot of property value that is tax-exempt: just over 40% of property value in the county is levied zero property tax. For the purposes of this discussion, I’m focusing on Cornell since this topic is most commonly discussed in regards to Cornell because of its size and influence.

Whenever the exemption is brought up, it always seems to carry a two-sided commentary that goes something like this:

“It’s unfair that Cornell’s monetary contribution to the City under the Memorandum of Understanding is so low, and it forces everyone else to pay higher property tax rates” -OR- “Cornell contributes so much to the community via its payrolls, student population, and programs so the property tax exemption is fair because of those benefits”

Both these viewpoints have merit, and they attempt to answer the same question: do Cornell’s positive externalities justify the gap in the public provision of services for Cornell versus what Cornell pays directly under the MOU?

I don’t know the answer, but my intention is to provide a rough snapshot of the situation in this article. In both cases, the reality is contingent on many complicated factors: even though Cornell only voluntarily pays a small share of the tax burden it would be charged if it weren’t exempt, it wouldn’t be fair to assume that everyone else’s tax rate is exactly higher by the exempted amount. As for the flip-side argument, Cornell’s local positive externalities are hard to measure, and include things that can’t feasibly be measured at all. In addition, Cornell’s full tax burden were it not exempt would be exorbitant, and clearly way beyond the value of public services it consumes.

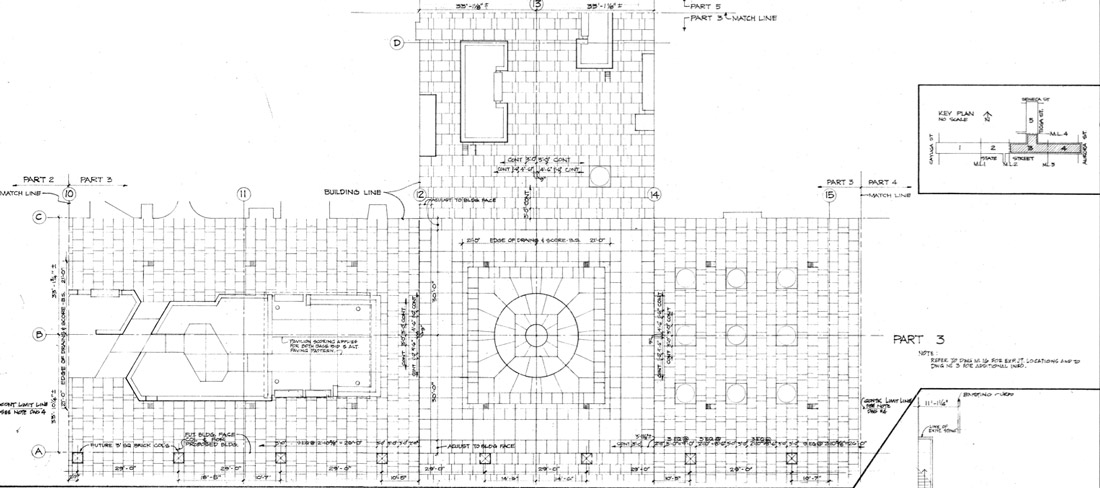

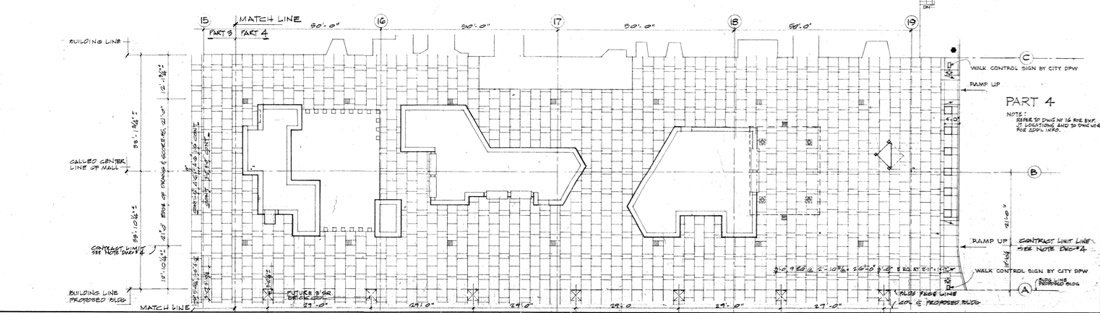

I ran a basic analysis below with the 2013 Tax Roll GIS data from the Tompkins County Department of Assessment to figure out what Cornell and Ithaca College would have been levied if they weren’t tax exempt. I ran filters for Owners, Roll Section, City/Town parcels, adjusted for duplicate objects, and then used the 2013 rates based on assessment value.

New York’s Real Property Tax Law Section 420-A (RPTL 420-a) defines the property tax exemption for Nonprofit organizations (including educational institutions) at the State level. At the federal level, income revenue is exempt due to the designation as a 501(c)(3) corporation. The federal not-for-profit status also allows for sales tax exemptions on many types of sales in various states; Cornell has exemptions in 14 states plus DC. The RPTL nonprofit exemption originally dates back to 1799, but the differences then versus now in the nature and practices of many nonprofits, and especially educational institutions are legion. Back then it was highly unlikely to afford the opportunity or the time to go to college, and institutions were small. Nowadays, both private and public universities have grown enormous, and tend to operate like businesses, competing internationally to attract customers to the products in education they offer. Tuition and fees certainly make-up a large portion of the operating revenue, but there are also other major sources (see operating revenue below, in this Year End 2012 financial statement).

For Cornell, tuition and fees accounts for about 28% of total operating revenue (and this most recent fiscal year shows an operating loss of over $158 million, although total net assets show a lesser decline on the consolidated statement further below). Keeping the tuition proportion low makes sense in order to attract students with financial aid, and also from a business-perspective for a diversified revenue structure. However, non-tuition-based revenues have been a point of contention for local taxpayers at Universities elsewhere.

The revenues from licensing intellectual property have landed Princeton University into another round of disputes with its New Jersey neighbors, and this time, the matter is in a New Jersey Tax Court, with residents claiming suit against both the University and the Town of Princeton. Cornell’s parcels account for about 60% of the exempt value of property in Tompkins County, and just over 70% of the exempt value in the City. See below for the exemption summaries in both the County and City.

Cornell University pays about $1.2 million a year to the City of Ithaca under the terms of the MOU (increase pegged to CPI until 2023), and it was about this time last year that Mayor Svante Myrick suggested Cornell increase its payment to $3 million. The same case was made back in 1995 under Mayor Benjamin Nichols, whom went to the extent of holding building permits for Cornell until negotiations progressed (under the premise of inadequate parking due to zoning), and meanwhile over a hundred construction workers demonstrated outside City Hall due to their inability to start work (New York Times articles below). Nichols was able to get an increase from $143,000 the current year to $250,000 the next fiscal year, and an escalation to $1 million to 2007. Taking a different approach, Mayor Alan Cohen negotiated in 2003 for the current 20-year MOU, which bumped-up Cornell’s payments further with the provision that Cornell would be treated equally and fairly under the planning and building approval process.

The long span of the tax exemption has indirectly supported Cornell’s construction of top-notch facilities, since these improvements on their land parcels are not taxed (although Cornell must pay building permit fees for construction, which is .7% of total construction costs). The long run expectation has been set, so it’s understandable for Cornell to operate very defensively in this regard. The consolidated statement below shows net land, building and equipment value at just over $3.3 billion as of June 30th, 2012. This will surely increase further as additional buildings come online (Gates Hall, Klarman Hall), and the future two million square foot Cornell NYC Tech Campus is developed on the 2.5 acres of Roosevelt Island.

One crucial point in this discussion is the consideration of the context in which Cornell operates. Cornell competes vigorously with other education institutions for customers internationally so its stance is naturally much different than the gross majority of businesses in Ithaca that compete regionally and locally. Not to say that Cornell is “above” local politics, but rather the opposite: Ithaca unfortunately has little to offer compared to a major metro area for many students. A commentator on Ithacating’s blog made a great point about this:

“I know many applicants don’t even consider Cornell because of its rural isolation – I definitely had no intention of coming here for college and I only applied for my PhD on the suggestion of an advisor who recommended some of the faculty. I would have never considered it over a school close to a major airport or rail line, even if that school were lower ranked. And it’s not just student preferences for these things that matter – if the school struggles to attract top faculty, that has an effect on student recruitment and selectivity as well.”

Ithaca’s a supremely nice place to live, but as far as major real-world opportunities (especially the sort that can be readily paired with a professional education), Ithaca has difficulty competing. The NYC Tech Campus is a natural and strategic reaction to the reality that proximity and mobility to outside opportunities matter, sometimes even more so than a degree. The Tech Campus will allow Cornell to compete in an environment where technological education paired with work outside of the classroom has become a highly-desired and necessary education program.

To get back to the point at hand though, what does Cornell contribute to the local community that would typically be outside the purview of other types of businesses/institutions?

I don’t have enough information to begin to quantify Cornell’s total positive externalities, but here’s a list of some major considerations:

-Sales tax exemption vs. use of local vendors for both Cornell and students: whatever Cornell cannot do in-house it must purchase from a vendor, and many of these vendors are companies located here. In addition, since Cornell brings a massive student population to town, many retail/service sectors benefit in sales, which are taxed through sales tax and indirectly through property tax on those businesses.

-Student housing: most of Cornell’s customers must actually live here, therefore one could logically count the revenues and pursuant property taxes of off-campus student housing as a positive externality (although this could be treated as a break-even in this context, since off-campus housing consumes public services conceivably equal to the property taxes paid). Not many types of businesses require their customers to relocate to their area of operation, so I think it’s justifiable to count this as an atypical externality when compared to a typical business. On the other hand, Cornell’s employee payrolls and pursuant taxes on their properties, local purchases, etc. don’t seem like a logical externality: most businesses would have their employees live locally anyways, so if Cornell were instead a large manufacturing operation, the same logic would apply.

-Tompkins County Cornell Cooperative Extension: out of an $8.5 million budget in 2012, Cornell contributed nearly $2 million, paired with Federal Sources (chart below)

-Cornell contributes about $829,000 a year to assist in funding TCAT (Tompkins Consolidated Area Transit, a not-for-profit bus operator), which is also equally-matched by the City and County (and Cornell employees and students benefit with a deep transit discount called OmniRide, in addition to free evening rides). The largest revenue chunk (36% of a total $12.7 million budget) comes from NYS taxpayers: the DOT’s State Operating Assistance Fund (STOA)

-Cornell operates its own police force of 54 sworn officers, and a total staff of 70. I’m not sure what it costs Cornell, but the City of Ithaca has 63 sworn officers, and the Ithaca Police Department’s total budget is $11.66 million in 2013.

-Back in 2008, Cornell announced a 10-year $20 million strategy for boosting local housing and transportation infrastructure through their Government and Community Relations Department. There are a number of programs run through this effort, but for the sake of simplicity, we could peg this value at ~$2 million a year.

I’m probably omitting something worth noting, so please correct me if I have. I’m obviously omitting non-local externalities like academic research, tech discoveries, etc., which are far beyond this scope and magnitude.

Given this information, if we were to tally-up the positive externalities above and compare with the gap in public services provided to Cornell minus the MOU, I think we’d end up with an answer showing that the positive externalities far outweigh the public service funding gap, but because of the functioning of the tax exemption, there’s a mismatch in value capture for public service. In an ideal world, the funding for public services should be tied directly to the beneficiaries of those services in the proportion that they benefit. The benefits of these positive externalities don’t necessarily accrue directly to the City and County’s bottom lines- more likely, they may indirectly.

I highly doubt Ithaca and Cornell would ever end up with a situation like that in Princeton, but perhaps the goal should be to follow positive examples elsewhere. Yale and New Haven’s town-gown relations are commonly held up as a cozy relationship, and examples can be drawn from many other places, since almost every other college town has this exact same battle over budgets.

I would ultimately argue that Cornell’s chief concern is not the financial implication of paying more, but that of autonomy. An institution the size of Cornell is probably more concerned with being able to control exactly what is done with its finances, so taxes to a municipality providing services is much less desirable than a situation in which Cornell has the power to either provide those services to itself, or have the ability to closely oversee or control how their tax spending is used.

Any further obligation under an MOU is an agreement that Cornell is signing for which it has zero legal obligation to do so. Given Cornell’s stance, I think a reasonable approach would be to find ways to utilize Cornell’s self-interest to local benefits that are in common. Cornell is concerned with safe housing, transit for employees and students, local student opportunities, attracting the brightest people, etc.- so a firm strategy would be to bring aligned objectives to the table, and start there. City and County services don’t pay for themselves, but without a legal obligation to pay them, Cornell should only have an interest in negotiating through shared objectives.

The utilization of tools like value capture (essentially LVT per marginal increase) could be useful, whereby a municipality creates a new or improved infrastructure service or public program, and the private land that benefits is taxed to account for the increased value of the land. In the case of land already exempt, we’re not talking about a land value tax, but instead, a negotiated agreement to help fund specific projects that would benefit both the City/County, and Cornell’s operations (TCAT is a perfect example). It would help to know Cornell’s share of the current ongoing public service costs, and also how the cost share is determined, which would probably provide another set of complications.

I have no doubt that the perspective of approaching Cornell through shared objectives is the stance of Mayor Myrick and other local officials faced with this reality every day. Local governments in college-towns may have tremendously difficult budget constraints, but also opportunities distinctly unique to those places as well. The proposed 2014 City Budget this next fiscal year has a projected 1.9% gap in expenses to revenues, and Tompkins County Administration has announced a recommended 3.5% property tax hike for next year.

I imagine Cornell will keep the MOU as-is, but it will be interesting to see whether or not this discussion crops up again this year, and how it is received by locals, students, and faculty.